- Home

- Parvez Sharma

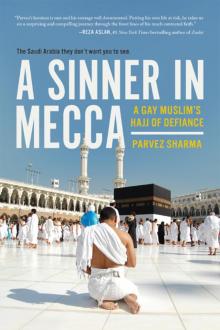

A Sinner in Mecca Page 3

A Sinner in Mecca Read online

Page 3

The public argument I made in interviews I gave in Beirut was simple: Nothing but homophobia could make Israel’s chief Sephardic rabbi and two other chief rabbis; the heads of the Roman Catholic, Armenian, and Greek Orthodox churches; and three senior Jerusalem imams sit together at the same table as they did in 2005 in a famous New York Times cover picture. These otherwise bitterly divided religious figures made probably their only public appearance together to protest that year’s ten-day Jerusalem World Pride Festival that would include a Pride Parade. During the parade, it was an ultra-Orthodox Haredi Jew who stabbed three marchers with a sharp kitchen knife. His name was Yishai Schlissel.

During a police interrogation, he described the motive behind his actions: “I came to murder on behalf of God. We can’t have such abomination in the country.” He was practically speaking like a Wahhabi cleric. Wahhabi Islam is the ultra-puritanical form of Islam in Saudi Arabia, with much influence in the rest of the Muslim world. Claims have been made that in Saudi Arabia Wahhabis are a minority. I disagree.

As I told a journalist at the time, this is what happened in my own India when religious Hindus and Muslims united publicly against lifting the gay “ban” in Article 377 of the Indian penal code. This article made “sodomy,” “carnal intercourse against the order of nature,” and “bestiality” part of a punishable list.

“Nothing better than a good old-fashioned round of gay-bashing to bring the Hindus and Muslims together,” I told him, trying to explain the similarities. This was because Lebanon had its own 377 in Article 534 of its penal code.

I hung out with members of the openly gay group Helem, funded mostly by European nonprofits. Like Istanbul, Beirut served as a waiting room for Middle Eastern gays seeking asylum in the West. Helem helped them to navigate a complex Lebanese bureaucracy for temporary visas. Although islands of tolerance like Acid existed in Beirut, nobody was waving rainbow flags from their apartment windows.

There was always the danger of government crackdowns. Local activists told me of retrogressive practices like rectal exams, which were common for men detained for “unnatural behavior.” Hardly a Provincetown, I thought to myself.

At the Turkish-style bathhouse Hammam al Agha, a lot of cruising was going on. In just a few years it would be raided. The anal-probes of the men arrested at the Plaza Cinema for “unnatural behavior” were soon to return. Helem was taking a strong stance on the freedoms that had not yet arrived constitutionally, religiously, or socially. There was no San Francisco–style Castro Street or New York’s Chelsea neighborhood to be found in Beirut. The activists at Helem were right about their perilous freedoms. Later, I gave them a bunch of unmarked DVDs of my film. They said some of them traveled regularly to Damascus, Aleppo, and Amman and would make sure the DVDs ended up in “the right hands.” I was thrilled—I had successfully managed to send DVDs of my contraband film to many Muslim countries including Pakistan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia. And there would be many more.

Fouad, a Palestinian-American writer and activist, invited me to a raucous party at his apartment in the Christian enclave of Achrafieh. He worked for the US-based pro-Palestine website “Electronic Intifada.” There I met fixers and filmmakers, correspondents and bankers—even a sixty-year-old former soprano. They drank, smoked hashish, and talked all night. I participated in the drinking but not the smoking. My one experience with hash as a younger man had left me paralyzed with paranoia. A twenty-something French woman performed an architectural analysis on Beirut’s downtown. She described it as plastic and soulless. It had been commissioned by the billionaire former Prime Minister of Lebanon Rafik Hariri.

We lingered on the balcony of the apartment. I rested my arm on a ledge and noticed that it was riddled with bullet holes.

“Bullets in Beirut,” I said.

“Par for the course,” she replied.

At 2 a.m., no one showed any signs of leaving. Sensing my exhaustion, the host’s sister, Sayida, approached us. She worked with Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

“Don’t worry,” she said. “This is normal. In Beirut we always party like it is the apocalypse tomorrow. You need another drink.” At the time I still drank alcohol. Most of the Muslims I knew also imbibed. I didn’t know it then but total sobriety lay in my not-so-distant future.

“Right now there are Israeli drones above us,” she continued. The fatalism of the Beirutis was familiar by now. Even if some or maybe all of the people at this party were not religious, they seemed to share the idea that “the end of days” was always just over your shoulder.

My Saudi friend Adham texted me one day while I was in Beirut. I had met him at an A Jihad for Love screening in Toronto in 2007. Since then we’d become great texting buddies. He lived in Jeddah, but the frequency of our correspondence meant he never seemed far away. “Only you know,” he had once said to me about his attraction to both men and women.

“Did you see this?” It was a link to an English-language Arab weekly called Egypt Today, read mostly by expats in Cairo. It was from 2008. Moez Masoud, a young Egyptian daa’y (caller to Islam) and media expert who had studied under the grand mufti of Egypt, Ali Gomaa, was quoted in this article about my film:

The [documentary] is correct in its use of the term of jihad but defines it incorrectly. When people who have homoerotic desires struggle against their inclinations, they are struggling against an act that satisfies their physical body but is against their spiritual self . . . jihad is to struggle in the cause of good. It’s a struggle for the sake of goodness, beauty, justice, and truth. Homoerotic activity is not a manifestation of these universal principles; it’s a violation of them and is in antithesis to the spiritual dimension. I love the title [of the movie] but when defined differently. We need to have jihad against extremism in society so we can learn to love the sinning person that is struggling, even though we hate their sin. And so, I too, call for a “jihad for love.”

Although he was not ready to welcome gays into the religion with open arms, it felt like Masoud was meeting me halfway.

“LOL!” I texted back, “He is calling for a jihad for love! Like really?! Anyway, why are you sending me such an old link?”

“I was googling you! I love Beirut btw. Kiss it frm me.”

Adham and I texted almost daily. Over the years we have physically only met a few times, but I count him as one of my closest friends. There is practically nothing I have not told him. Just a few days after the Egypt protests—which I reported on extensively—erupted, I asked him rhetorically if revolution was coming to Riyadh. He had texted back, “Are you kidding me? Parvez, unlike the Egyptians, the Tunisians, the Egyptians, and others who may follow, we Saudis just don’t suffer enough.” At the time, I thought that was a very succinct way to address a fairly complicated question. He continued, “It’s always been Al Saud. It will always be Al Saud.”

Over the years, just like mine, Adham’s life changed. Just months before my Beirut schlep he acquired a fiancée. My friendship with the bisexual Adham is unusual, and I never asked if he had ever acted on his desires. He would never reveal it to his family. It was cultural. I understood because I grew up in small-town India. I have never dared to say the three words to my dad—I am gay. For Muslims like Adham and me, as far as family was concerned, it was “don’t ask, don’t tell,” which suited all parties.

In that 2010 Beirut winter, Adham, as always, was a daily presence in my life. By extension it seemed that Saudi Arabia itself was a daily presence as well. The #Jan25 hashtag was still not the most-used on the planet, and even Tunisia was a few weeks away, but there “seems to be some unease here, I don’t know why,” he once texted me from a Dunkin’ Donuts in Jeddah, a popular cruising area for gay men. I wondered how long Adham could sustain all the charades, but I refrained from upsetting him.

Adham’s engagement to Zubeida, a second cousin, was “arranged” by his pious mother, in a practice familiar to all Muslims. Surprisingly, the two are still not married. Zubeida and Adham

only met when she visited family in Jeddah or when he went to Riyadh. Meeting itself was a complex negotiation because of Wahhabi views against ikhtilat (gender mixing), which was reliably the most explosive subject in the kingdom.

Zubeida attended Thursday Quran-study circles. The Prophet, it is said, called them “Halaqah.” Religious as she was, Zubeida was completing a PhD at the Princess Nora University in Riyadh, where her family lived. Opened a few months after bin Laden’s death, PNU, as the Saudis called it, was the largest and “most modern” female university in the world, they boasted. At its opening, King Abdullah and other male dignitaries sat in a mixed-company room with women whose faces were uncovered. The clerics were furious. But Abdullah stood his ground. And yet in 2012 this same king introduced a system whereby husbands were “informed” on SMS when their wives or children were leaving the country.

PNU’s campus was proof of the country’s need for good architects, beyond those supplied by the bin Laden family. This was a tasteless marble, glass, granite, and central air structure. Women would enter wearing ordinary sneakers; their abayas when taken off would expose heavily made-up faces and stilettos. An abaya is a baggy black sack that covers every inch of a woman’s body. Some abaya-clad women, like a female mutawa (religious police), will also cover their feet with socks and wear black gloves.

There is much erotic power in covered female flesh. A good example is Rita Hayworth’s one-gloved striptease, singing, “Put the blame on Mame” as Gilda in the 1946 Hollywood noir of the same name. It lives forever in YouTube fame. Just in the act of taking off her glove, Hayworth becomes hypersexualized, with every straight man in that Buenos Aires nightclub mentally undressing her. A woman in an abaya or other styles of veiling is also a hypersexualized entity. A carefully revealed ankle, when the mutaween are not looking, is enough to stir lust. There is nothing more threatening than a sliver of female hair or ankle to the discipline of the male armies of the devout, in conservative Muslim minds, such as the duplicitous enforcers of morality in Saudi Arabia—the mutaween.

Adham often probes to determine whether Zubeida has a mind of her own. About the ruling Sauds, she had said, “We don’t talk about these things. But in my opinion our king is from God’s will. He listens to us.”

Were women like Zubeida the majority? Never challenging the status quo? Did they truly believe that if they held the hand of their mahram (a male guardian from within her direct family) they could achieve stellar education and careers?

I asked Adham when the wedding was. I was eager to attend. He said it would be a while yet because “PhD students take forever.” I gasped when I learned what her thesis was: “Sharia in the twenty-first century.” This “super-pious” woman entering an “arranged marriage” with her closeted bisexual fiancé was certainly obeying the absolute command to exercise intellect that lay at the very birth of the Quran. Muhammad, its vessel of revelation, was illiterate, after all, a condition Zubeida would clearly not tolerate.

“I would die to read her thesis,” I said to Adham.

“ISA I will send it to you when she is finally done.” He was using the shorthand for everyday Arab terms as Muslims often do. An ISA is Inshallah (“If God wills”).

“I understand why your shameless Saudis love to summer here,” I texted Adham. The more I walked its streets the more I loved the city. I felt that, except for my beloved Istanbul, Beirut was the most cosmopolitan Muslim environment I had ever experienced, though many Beirutis would be offended at the characterization of their city as Muslim. It recalled the openness that I imagined permeated Muslim societies during centuries of Ottoman rule. As I left a café locals called “Facebook,” with an exact replica of a “like” as its prominently displayed sign, a writer friend informed me, “I think this may be the only café called ‘Facebook’ in the world.”

In central Beirut, a few hours after Adham had texted me about Zubeida’s surely fiery PhD topic, one of two evening screenings for my film was held in a fashionable café-turned-screening-room. It was packed to the rafters. The post-film question-and-answer session went on for at least an hour, probably more. I tried to be witty, saying, “Clearly Hizbullah were not invited to this.” Just a few nervous laughs. This was complicated territory and jokes about this audience’s fellow inhabitants were not welcome. I was learning fast and my mind kept on drifting to Adham’s revelation about Zubeida’s thesis.

An audience member spoke up. “Why are these people in your film so religious? In Lebanese culture religion traumatizing gay people like this is unheard of.”

I responded, “Thanks. That’s an interesting way to look at the film. I hope the film answered your question? I always hope that the film speaks for itself, better than even I can.” She persisted and I said, “Maybe things will change? These days we even have Saudi women doing PhDs!” Raucous laughter. I didn’t offer the stock Islam 101–style responses I used with Western audiences. I was being hypocritical. I avoided a discussion I would have welcomed in any other country. This was probably because I didn’t know enough about how religion lived in the twenty-first century Beiruti environment. I already knew well the history of religion’s role as the deepest possible divide in this civil war–torn country. But I hadn’t really taken up the opportunity for any contemporary religious discussion with anyone, even Rafik, for example, that night we walked on the corniche.

Post-screening, Aisha, a butch lesbian activist, told me, “I loved it! In any case, how much of Beirut have you seen? Will you allow me to be a guide to something no tourist gets to see?” I took up her offer and we arranged to meet at noon at my hotel the next day.

“I have been waking up late, I must confess,” I said to her. “This is such a city of the night.”

What I didn’t tell her was that one of the reasons I couldn’t meet early was that my hookup the previous night had deprived me of sleep. He was a tongue-tied Saudi Grindr trick who called himself Ahmad. I always wanted to know something about the person I was hooking up with, so there was some semblance of honesty in a purely sexual encounter neither of us would probably tell anyone about. Few people realize the enormity of promiscuity amongst gay men compared to other sexualities and genders.

Ahmad was ready to cancel when I told him about my film. “I don’t want to be interviewed about all this, man,” he texted. I told him he had nothing to fear because the film had already been made. He traveled frequently from Jeddah to Beirut for a financial group he said he worked for. As he left that night I gave him an unlabeled DVD of the film. I used to do this often, sending DVDs through friends (and in this case a trick!) going back to Muslim countries, where the film could never be seen officially. Two years before I came to Beirut, a Dubai gay friend of mine, Salman, whom I met at American University when I was a professor and student there, emailed and said he had been to Lahore in Pakistan and seen pirated DVDs of the film being sold on the streets of the bustling Anarkali market. Salman had already made many copies for friends in and around Dubai and once organized a private screening in his living room. It was an “Underground Railroad” of distribution I was trying to build, without actually putting the film on YouTube.

I had already added Aisha as a Facebook friend when we met the next morning. She took me on a tour of the subversive graffiti that lined the walls that had once delineated the outer boundaries of the city and the beginning of its Armenian quarters. One said “Berlin” in Arabic, alluding to that city’s divisive wall. Snow White brandished a Kalashnikov in another with the words “Say no to Lookism” in English spray-painted next to her. But why the gun? I thought to myself.

“That is about the obsession of the Lebanese for boob jobs, tummy tucks, liposuction, and general desire to be flashy and beautiful all the time,” she explained with obvious disgust.

Aisha also told me that both Lebanese sexes were also obsessed with nose jobs. I found a lot of Lookism graffiti. Right next to it, some of Hizbullah’s rallying cries were displayed in beautiful Arabic calligraphy. �

��God let us meet Husayn in the afterlife,” it said, referring to one of the most revered Shia imams and the Prophet’s grandson. For Shias, Husayn was the second caliph, right after Ali. For Sunnis, the second caliph after Ali was Abu Bakr. And in this deceptively simple fact about Muhammad’s lineage and succession lay the beginning of a sectarian Islam bloodily divided into Shia and Sunni. As I studied the Hizbullah graffiti on this wall, I was reminded that there was nothing simple about this deep divide that had finessed into two essentially separate religions in the centuries following the Prophet’s death.

“I hate them,” Aisha said, breaking my reverie as she referred to Hizbullah.

I had always been fascinated by graffiti in the bathrooms and streets of foreign cities. For me, the graffiti were always an indicator to how a society actually lived. I felt unique access to the minds of the city’s individuals whenever I studied the graffiti.

We drove down 22 November Avenue, and Aisha pointed to what she called “the Horsh.” The Horsh El Snoubar was a legendary park the Israelis had bombed to smithereens in 1982.

“For reasons we Beirutis have never understood,” said Aisha. “It was always locked up since I was a child.” This park had been off-limits to mostly everyone for almost twenty-five years, even though it had been reconstructed after the fifteen-year-long Lebanese Civil War ended in 1990. Aisha told me that Beirutis wanting to visit the park had to apply for special permits, and that it was apparently easier for Western tourists to get in.

“This is very strange,” I told her. “A locked-up park? But let me tell you that in Manhattan we, too, have a locked-up park called Gramercy Park. It’s only for residents who live around it.”

A Sinner in Mecca

A Sinner in Mecca